ICEFIRELAND

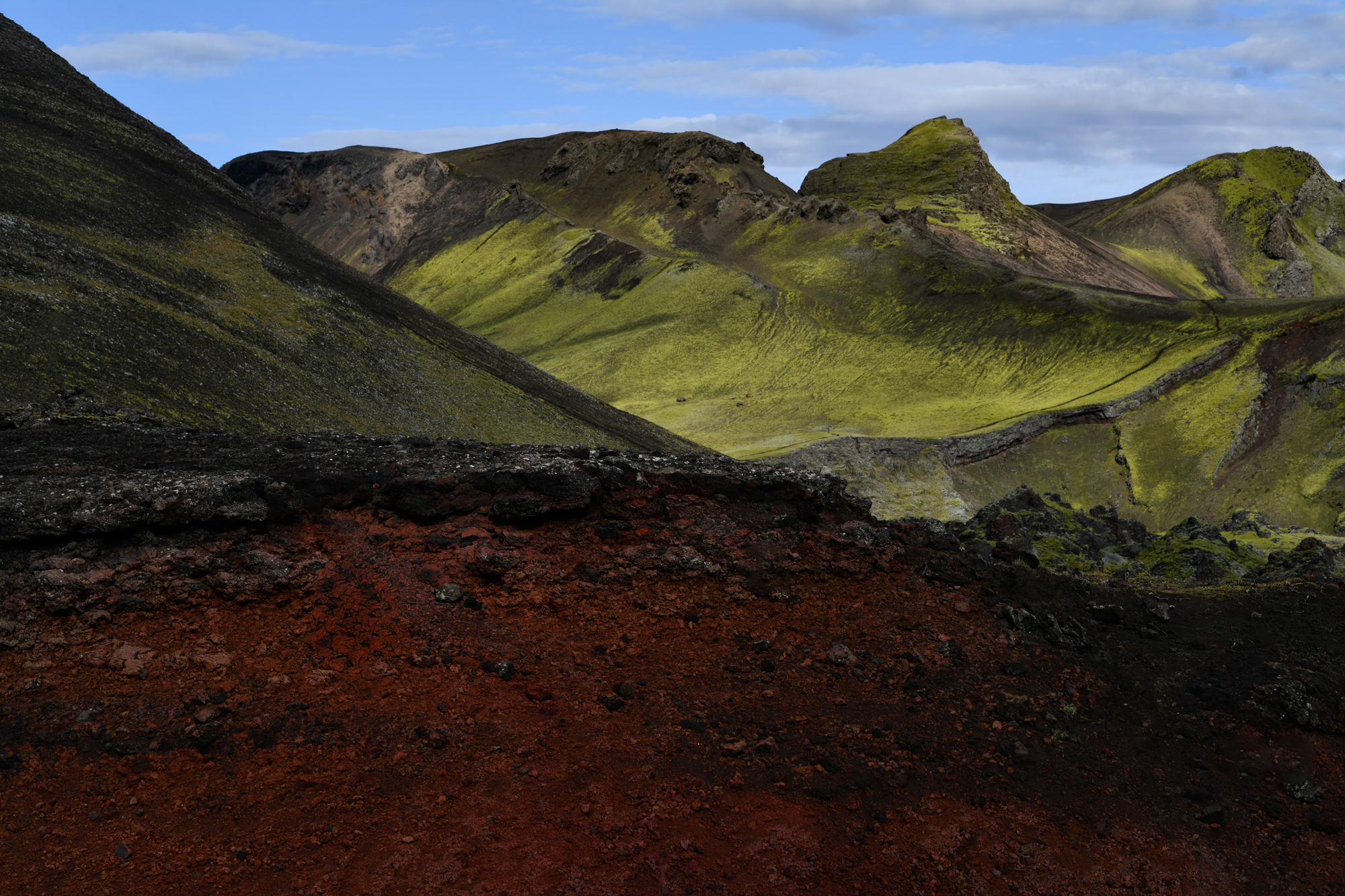

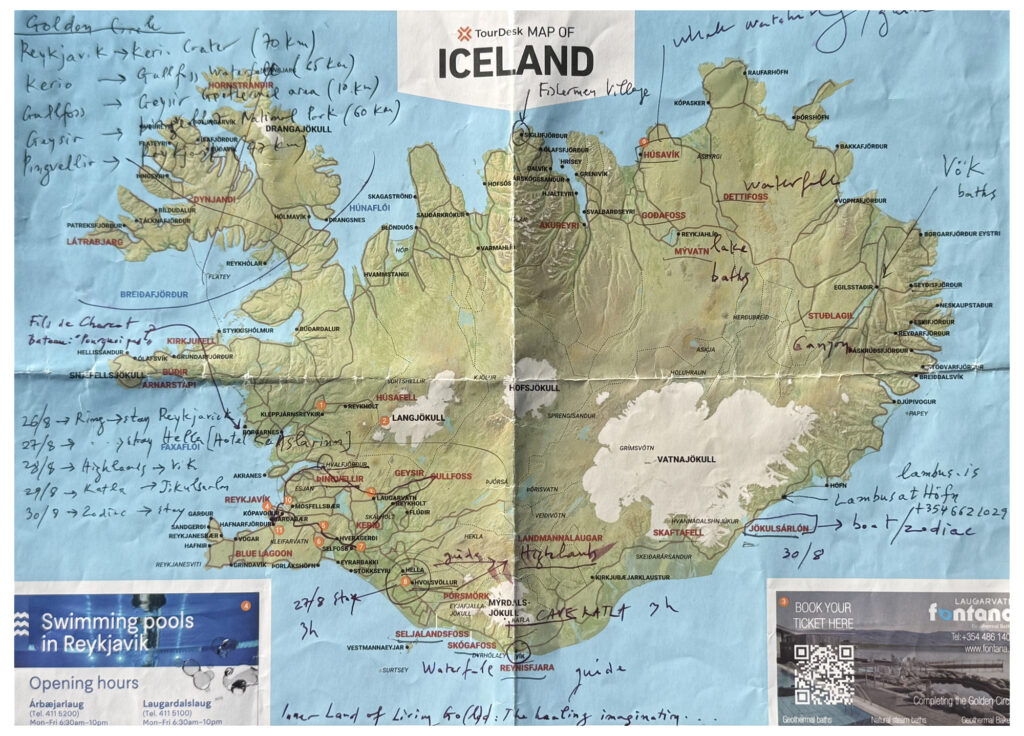

Why does someone choose to travel to “improbable” places? To confront the unknown, the strange, the uncanny — to be pushed out of their comfort zone and given the chance to wrestle with the dark fields of Nature’s and Humanity’s history. Wandering across glaciers and volcanic highlands, just like wandering through the desert, becomes an inward vortex, a trembling oscillation between the beautiful and the terrifying; an ecstasy, an exposure to the overwhelming knowledge of the universe’s eternal alternation between the beginning and the end of the world. If you can endure that “openness,” a journey to Iceland is not a visit but a return to what is essential, to all that is “worthy of being.”